“Building a Bad B**ch”: SDSU student redefines Black femininity through hip-hop

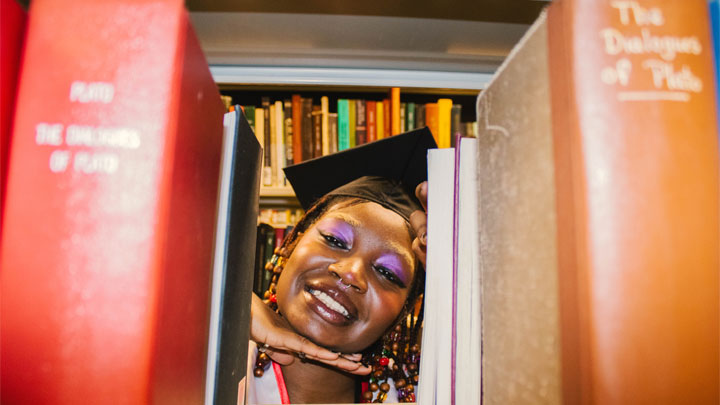

SDSU graduate student Naiima Paul examines Doechii and Flo Milli’s lyrics to show how Black women rappers reclaim language, challenge stereotypes and reshape representations of femininity through hip-hop–blending personal identity with academic research.

When SDSU graduate student Naiima Paul tells people she’s writing her master’s thesis about the lyrics of rappers Doechii and Flo Milli, she’s often expecting to get raised eyebrows.

Paul, now in her second year of San Diego State’s Master’s in Mass Communication program, has built her research around an idea that’s both bold and personal: that rap lyrics, which are often dismissed as vulgar or superficial, can tell complex stories about Black femininity, representation and resistance.

Paul’s path to graduate research began in the same halls where she earned her undergraduate degree.

“I did my undergrad at SDSU, and the JMS department just made me feel seen,” she said. “I had professors who really opened my eyes to how media could be studied, how pop culture, race and gender could actually be part of academic research.”

Her curiosity deepened after taking a class with Dr. Smith, where she encountered a scholarly article analyzing Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s WAP through a Black feminist lens.

“The title literally had the word ‘pu**y’ in it,” Paul recalled. “It shocked me at first, but reading it was life-changing. I realized, this is research. This is valid. You can study the music we actually listen to and uncover something powerful about society.”

That moment sparked what would become her thesis: a textual and discourse analysis of how modern Black women rappers, particularly Doechii and Flo Milli, construct identity and challenge stereotypes through their lyrics.

At the heart of Paul’s research is the concept of “subversive reclamation,” i.e. taking words historically used against women and transforming them into expressions of strength.

“In hip-hop feminism, there’s this idea that when a rapper calls herself a ‘bad bitch,’ she’s not buying into oppression she’s flipping it,” Paul explained. “She’s saying, ‘You can’t use this word to control me anymore. I own it now.’”

Through a discourse analysis approach, Paul dissects how words like “b**ch” and “hot girl” function within rap’s larger cultural context, tracing their evolution from insults to affirmations of self-worth and autonomy.

“It’s about understanding that these lyrics don’t exist in a vacuum,” she said. “They’re connected to centuries of stereotypes about Black women’s sexuality and respectability. When Doechii or Flo Milli use that language, they’re rewriting the script.”

Like many graduate students, Paul juggles a full plate. She works as a teaching assistant, manages another on-campus job, and still finds time to write, read and listen to new music for her research.

Her support system, friends, professors and family back home in Los Angeles help her keep grounded.

“They’ve always believed in me, even when I doubted myself,” she said. “When I got into the master’s program, I felt like I was finally where I was supposed to be.”

Though Paul’s research is still in its early stages, she already sees how her work could contribute to broader conversations in media studies and Black feminist scholarship.

For her, it’s not just an academic pursuit. It’s a reflection of her world, her community, her playlists and her identity.

“These songs shape how we see ourselves,” she said. “They influence how Black women talk about confidence, power, and femininity. That deserves to be studied.”

When asked to sum up her thesis in three words, Paul paused, smiled, and said:

“Personal, representational, experimental.”

Then she laughed. “And maybe ‘unfinished,’ because I’m still working on it.”

Whether it’s finished or not, Paul’s work is already helping redefine what counts as serious research, proving that the sounds of today’s rap culture can echo powerfully through academia.